According to the Bank for International Settlements, in mid-June last year all global OTC contracts outstanding were still unimaginably large at $640 trillion, a massive sum in anyone’s book. It is unlikely to have changed much by today. But in bank balance sheets only a net figure is usually shown, and you have to search the notes to financial statements to find evidence of gross exposure. It is the gross that matters, because each contract bears counterparty risk, sometimes involving several parties, and derivative payment failures could make the payment failures now evident in disrupted industrial supply chains look like small beer.

Deutsche Bank’s 2019 balance sheet gives us an excellent example of how they are accounted for in commercial banks. It conceals derivative exposure under the headings “Trading assets” and “Trading liabilities” on the balance sheet. You have to go into the notes to discover that under Trading assets, derivative financial instruments total €80.848bn, and under Trading liabilities, derivative financial instruments total €81.910bn, a difference of €1.062bn This is relatively trivial for a bank with a balance sheet of €777bn.

But wait, there is another table that breaks derivative exposure down even further into categories, and it turns out the earlier figures are consolidated totals. The true total of OTC derivatives and exchange traded derivatives to which the bank is exposed is €37.121 trillion. That is nearly thirty-five thousand times the €1.062bn netted difference in the balance sheet. And when you bear in mind that valuing OTC derivatives is somewhat subjective, or as the cynics say, mark to myth, it invalidates the valuation exercise.

Clearly, by taking the mildest of a positive approach to derivatives held as assets, and a slightly more conservative approach to valuing derivatives on the liabilities side, that 35,000:1 leverage at the balance sheet level can make an enormous difference.

Now let us take our imagination a little further. A large number of these derivatives will have commercial entities as counterparties, businesses that have been shut down by the coronavirus since the balance sheet date. With the German economy already heading into recession before the coronavirus closed down much of the global economy, Deutsche Bank’s risk of losses arising from its derivative position could turn out to be in the trillions, not the one billion netted difference shown on the balance sheet.

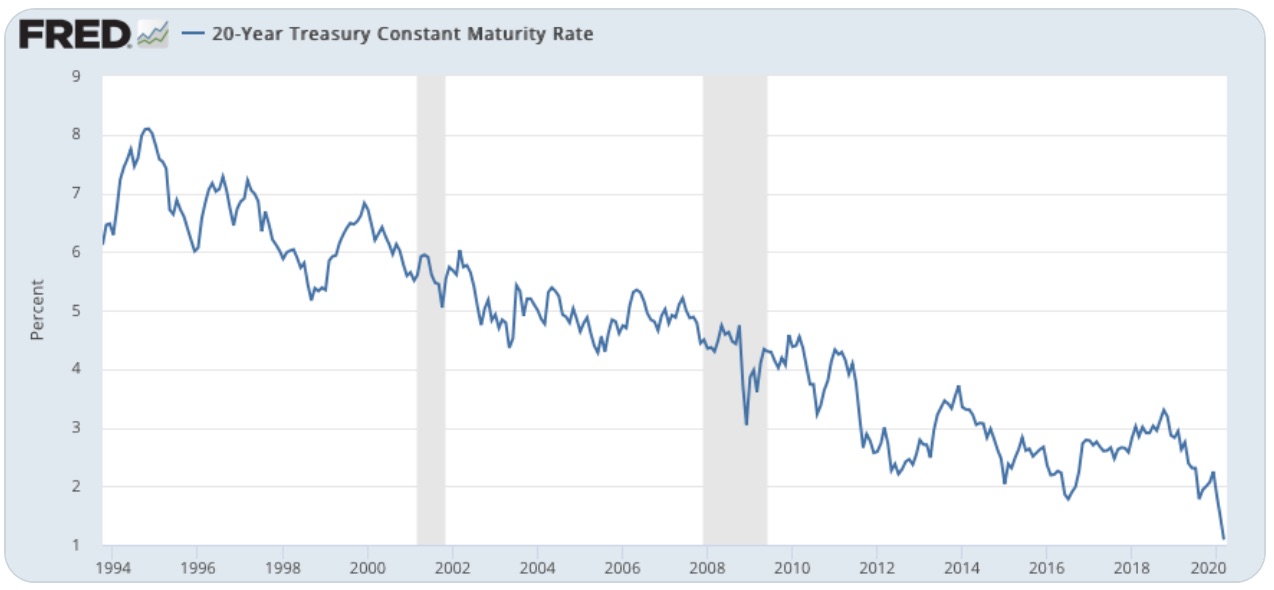

Not only is there the emergence of counterparty failures to deal with, but there are ever-changing fair values, which will particularly reflect interest rate spreads increasing for Deutsche Bank’s €30.25 trillion interest rate-linked derivatives. We cannot know whether it is net positive or negative for shareholders. And with balance sheet gearing of assets 22 times larger than share capital very little change could wipe them out.

Deutsche Bank is not alone in presenting derivative risk in this manner: it is the elephant in many bank boardrooms. As a weak link, Deutsche is a relevant illustration of risks in the banking system. Since the Lehman crisis, its senior management has been on the back foot, retreating from businesses they could neither control nor understand. They have also made very public mistakes in precious metals, which is our next topic.

Gold derivatives in crisis

While a struggling bank like Deutsche provides us with a laboratory experiment for how a derivative virus can kill a bank, we are now seeing it kill off bullion banks in real time. A rising gold price, out of the control normally imposed by expandable derivatives, has effectively gone bid only in any size. We are told this is due to COVID-19 shutting mines and refineries and disrupting logistics, and so is purely temporary. The LBMA and CME which runs Comex have been issuing calming statements and even announced the introduction of a new 400-ounce gold futures contract alleged to ease the supply shortage.

In short, the gold derivative establishment is panicking. The swaps position on Comex shows why.

With their net short position in very dangerous territory, Comex swaps are badly wrongfooted at a time when the Fed and other central banks have announced unlimited monetary inflation, signalling a paradigm shift in the relationship between sound and unsound money. For ease of reference and to understand their relevance, a swap dealer is defined by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which collates the figures, as follows:

An entity that deals primarily in swaps for a commodity and uses the futures markets to manage or hedge risks associated with those swap transactions. The swap dealer’s counterparties may be speculative traders, like hedge funds, or traditional commercial clients that are managing risk arising from their dealings in the physical commodity.

Therefore, a swap dealer is one that operates across derivative markets, and typically will trade in London forwards as well as on Comex. In a nutshell, it describes a bullion bank’s trading desk.

In a further piece of disinformation this week, Jeff Christian, head of CPM Group, in an obviously staged interview for MacroVoices claimed that traders in London were forced by their banks to cover trading risk in the futures market as a condition of their funding. The implication was shorts on Comex are matched to longs in London’s forward market and therefore not a problem. This may be true of an independent trader looking for arbitrage opportunities between markets but is not how it works in a bank.

While a struggling bank like Deutsche provides us with a laboratory experiment for how a derivative virus can kill a bank, we are now seeing it kill off bullion banks in real time. A rising gold price, out of the control normally imposed by expandable derivatives, has effectively gone bid only in any size. We are told this is due to COVID-19 shutting mines and refineries and disrupting logistics, and so is purely temporary. The LBMA and CME which runs Comex have been issuing calming statements and even announced the introduction of a new 400-ounce gold futures contract alleged to ease the supply shortage.

In short, the gold derivative establishment is panicking. The swaps position on Comex shows why.

With their net short position in very dangerous territory, Comex swaps are badly wrongfooted at a time when the Fed and other central banks have announced unlimited monetary inflation, signalling a paradigm shift in the relationship between sound and unsound money. For ease of reference and to understand their relevance, a swap dealer is defined by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which collates the figures, as follows:

An entity that deals primarily in swaps for a commodity and uses the futures markets to manage or hedge risks associated with those swap transactions. The swap dealer’s counterparties may be speculative traders, like hedge funds, or traditional commercial clients that are managing risk arising from their dealings in the physical commodity.

Therefore, a swap dealer is one that operates across derivative markets, and typically will trade in London forwards as well as on Comex. In a nutshell, it describes a bullion bank’s trading desk.

In a further piece of disinformation this week, Jeff Christian, head of CPM Group, in an obviously staged interview for MacroVoices claimed that traders in London were forced by their banks to cover trading risk in the futures market as a condition of their funding. The implication was shorts on Comex are matched to longs in London’s forward market and therefore not a problem. This may be true of an independent trader looking for arbitrage opportunities between markets but is not how it works in a bank.

- Source, Goldmoney